CCR5

| editar |

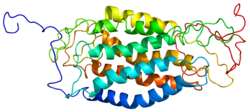

C-C receptor quimiocina tipo 5 também conhecida como CCR5 é uma proteína que nos humanos é codificada pelo gene CCR5. CCR5 é membro da família de receptores beta quemoquina das proteínas das membranas integrais.[1][2] O alelo CCR5delta32 resulta numa proteina que fica presa à membrana do retículo endoplasmático e não consegue se alojar na membrana plasmática. Como essa proteína é o sitio primário de ligação do vírus HIV com as células T, sem o receptor exposto na membrana o vírus não consegue infectar a célula, tornando a pessoa com esse alelo em homozigose imune ao HIV. Quando em heterozigose o desenvolvimento da doença é mais lento, mas eventualmente o paciente desenvolve a AIDS

HIV[editar | editar código-fonte]

O HIV utiliza a CCR5 ou CXCR4 como co-receptor para entrar na célula. Vários receptores quemoquina podem funcionar como co-receptores virais, mas é provável que o CCR5 seja fisiologicamente o mais importante co-receptor durante a infecção.

CCR5-Δ32[editar | editar código-fonte]

CCR5-Δ32 (ou CCR5-D32 ou CCR5 delta 32) é uma variante genética do CCR5.[3][4]

A mutação CCR5-Δ32 é uma mutação por deleção, visto que são eliminadas bases nitrogenadas da cadeia de DNA que codifica o gene, contribuindo para que a proteína CCR5 seja não funcional.

Como a vírus VIH-1 necessita de uma proteína CCR5 funcional para entrar na célula, a mutação CCR5-Δ32 irá reduzir o risco de infeção a este vírus.

Frequência da mutação CCR5-Δ32[editar | editar código-fonte]

A mutação CCR5-Δ32 é mais comum nos países do norte da Europa.[5]

Interações[editar | editar código-fonte]

A CCR5 interage com a CCL5[6][7][8] e CCL3L1.[9][7]

Referências

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference

- ↑ Samson M, Labbe O, Mollereau C, Vassart G, Parmentier M (1996). «Molecular cloning and functional expression of a new human CC-chemokine receptor gene». Biochemistry. 35 (11): 3362–7. PMID 8639485. doi:10.1021/bi952950g

- ↑ Galvani AP, Slatkin M (2003). «Evaluating plague and smallpox as historical selective pressures for the CCR5-Delta 32 HIV-resistance allele». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (25): 15276–9. PMC 299980

. PMID 14645720. doi:10.1073/pnas.2435085100

. PMID 14645720. doi:10.1073/pnas.2435085100

- ↑ Stephens JC, Reich DE, Goldstein DB; et al. (1998). «Dating the origin of the CCR5-Delta32 AIDS-resistance allele by the coalescence of haplotypes». Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62 (6): 1507–15. PMC 1377146

. PMID 9585595. doi:10.1086/301867

. PMID 9585595. doi:10.1086/301867

- ↑ Lucotte, G. (1 de setembro de 2001). «Distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion in West Europe. A hypothesis about the possible dispersion of the mutation by the Vikings in historical times». Human Immunology. 62 (9): 933–936. ISSN 0198-8859. PMID 11543895

- ↑ Slimani, Hocine; Charnaux Nathalie, Mbemba Elisabeth, Saffar Line, Vassy Roger, Vita Claudio, Gattegno Liliane (2003). «Interaction of RANTES with syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 expressed by human primary macrophages». Netherlands. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1617 (1-2): 80–8. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 14637022

- ↑ a b Struyf, S; Menten P, Lenaerts J P, Put W, D'Haese A, De Clercq E, Schols D, Proost P, Van Damme J (2001). «Diverging binding capacities of natural LD78beta isoforms of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha to the CC chemokine receptors 1, 3 and 5 affect their anti-HIV-1 activity and chemotactic potencies for neutrophils and eosinophils». Germany. Eur. J. Immunol. 31 (7): 2170–8. ISSN 0014-2980. PMID 11449371. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2170::AID-IMMU2170>3.0.CO;2-D

- ↑ Proudfoot, A E; Fritchley S, Borlat F, Shaw J P, Vilbois F, Zwahlen C, Trkola A, Marchant D, Clapham P R, Wells T N (2001). «The BBXB motif of RANTES is the principal site for heparin binding and controls receptor selectivity». United States. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (14): 10620–6. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 11116158. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010867200

- ↑ Miyakawa, Toshikazu; Obaru Kenshi, Maeda Kenji, Harada Shigeyoshi, Mitsuya Hiroaki (2002). «Identification of amino acid residues critical for LD78beta, a variant of human macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha, binding to CCR5 and inhibition of R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication». United States. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (7): 4649–55. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 11734558. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109198200

Leitura de apoio[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Wilkinson D (1997). «Cofactors provide the entry keys. HIV-1». Curr. Biol. 6 (9): 1051–3. PMID 8805353. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)70661-1

- Broder CC, Dimitrov DS (1997). «HIV and the 7-transmembrane domain receptors». Pathobiology. 64 (4): 171–9. PMID 9031325. doi:10.1159/000164032

- Choe H, Martin KA, Farzan M; et al. (1998). «Structural interactions between chemokine receptors, gp120 Env and CD4». Semin. Immunol. 10 (3): 249–57. PMID 9653051. doi:10.1006/smim.1998.0127

- Sheppard HW, Celum C, Michael NL; et al. (2002). «HIV-1 infection in individuals with the CCR5-Delta32/Delta32 genotype: acquisition of syncytium-inducing virus at seroconversion». J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 29 (3): 307–13. PMID 11873082

- Freedman BD, Liu QH, Del Corno M, Collman RG (2004). «HIV-1 gp120 chemokine receptor-mediated signaling in human macrophages». Immunol. Res. 27 (2-3): 261–76. PMID 12857973. doi:10.1385/IR:27:2-3:261

- Esté JA (2004). «Virus entry as a target for anti-HIV intervention». Curr. Med. Chem. 10 (17): 1617–32. PMID 12871111. doi:10.2174/0929867033457098

- Gallo SA, Finnegan CM, Viard M; et al. (2003). «The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction». Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1614 (1): 36–50. PMID 12873764. doi:10.1016/S0005-2736(03)00161-5

- Zaitseva M, Peden K, Golding H (2003). «HIV coreceptors: role of structure, posttranslational modifications, and internalization in viral-cell fusion and as targets for entry inhibitors». Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1614 (1): 51–61. PMID 12873765. doi:10.1016/S0005-2736(03)00162-7

- Lee C, Liu QH, Tomkowicz B; et al. (2004). «Macrophage activation through CCR5- and CXCR4-mediated gp120-elicited signaling pathways». J. Leukoc. Biol. 74 (5): 676–82. PMID 12960231. doi:10.1189/jlb.0503206

- Yi Y, Lee C, Liu QH; et al. (2004). «Chemokine receptor utilization and macrophage signaling by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120: Implications for neuropathogenesis». J. Neurovirol. 10 Suppl 1: 91–6. PMID 14982745

- Seibert C, Sakmar TP (2004). «Small-molecule antagonists of CCR5 and CXCR4: a promising new class of anti-HIV-1 drugs». Curr. Pharm. Des. 10 (17): 2041–62. PMID 15279544. doi:10.2174/1381612043384312

- Cutler CW, Jotwani R (2006). «Oral mucosal expression of HIV-1 receptors, co-receptors, and alpha-defensins: tableau of resistance or susceptibility to HIV infection?». Adv. Dent. Res. 19 (1): 49–51. PMID 16672549. doi:10.1177/154407370601900110

- Ajuebor MN, Carey JA, Swain MG (2006). «CCR5 in T cell-mediated liver diseases: what's going on?». J. Immunol. 177 (4): 2039–45. PMID 16887960

- Lipp M, Müller G (2006). «Shaping up adaptive immunity: the impact of CCR7 and CXCR5 on lymphocyte trafficking». Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pathologie. 87: 90–101. PMID 16888899

- Balistreri CR, Caruso C, Grimaldi MP; et al. (2007). «CCR5 receptor: biologic and genetic implications in age-related diseases». Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1100: 162–72. PMID 17460174. doi:10.1196/annals.1395.014

- Madsen HO, Poulsen K, Dahl O; et al. (1990). «Retropseudogenes constitute the major part of the human elongation factor 1 alpha gene family». Nucleic Acids Res. 18 (6): 1513–6. PMC 330519

. PMID 2183196. doi:10.1093/nar/18.6.1513

. PMID 2183196. doi:10.1093/nar/18.6.1513 - Uetsuki T, Naito A, Nagata S, Kaziro Y (1989). «Isolation and characterization of the human chromosomal gene for polypeptide chain elongation factor-1 alpha». J. Biol. Chem. 264 (10): 5791–8. PMID 2564392

- Whiteheart SW, Shenbagamurthi P, Chen L; et al. (1989). «Murine elongation factor 1 alpha (EF-1 alpha) is posttranslationally modified by novel amide-linked ethanolamine-phosphoglycerol moieties. Addition of ethanolamine-phosphoglycerol to specific glutamic acid residues on EF-1 alpha». J. Biol. Chem. 264 (24): 14334–41. PMID 2569467

- Ann DK, Wu MM, Huang T; et al. (1988). «Retinol-regulated gene expression in human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Enhanced expression of elongation factor EF-1 alpha». J. Biol. Chem. 263 (8): 3546–9. PMID 3346208

- Brands JH, Maassen JA, van Hemert FJ; et al. (1986). «The primary structure of the alpha subunit of human elongation factor 1. Structural aspects of guanine-nucleotide-binding sites». Eur. J. Biochem. 155 (1): 167–71. PMID 3512269. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09472.x