Usuária:Beria/Bandeira de Portugal

| Bandeira de Portugal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aplicação | |

| Proporção | 2:3 |

| Adoção | 30 de Junho de 1911 |

| Tipo | nacionais |

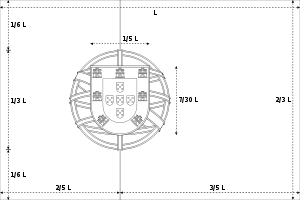

A bandeira de Portugal é um rectângulo com proporções 2:3, dividido verticalmente em verde (a 2/5 do comprimento) e vermelho (3/5). Quando desfraldada, a parte verde fica do lado da tralha, ou do lado esquerdo quando representada graficamente. Centrado na linha de separação entre o verde e o vermelho está o brasão de armas de Portugal, consistindo numa esfera armilar sobreposta pelo tradicional escudo português, de prata, com cinco escudetes de azul carregados de cinco besantes de prata e bordadura de vermelho, com sete castelos de ouro. A bandeira foi oficialmente adoptada a 30 de Junho de 1911, mas era já usada desde a Proclamação da República Portuguesa, a 5 de Outubro de 1910.

O significado da Bandeira[editar | editar código-fonte]

A bandeira tem um significado republicano e nacionalista. A comissão encarregada da sua criação explica a inclusão do verde por ser a cor da esperança e por estar ligada à revolta republicana de 31 de Janeiro de 1891. Segundo a mesma comissão, o vermelho é a cor combativa, quente, viril, por excelência. É a cor da conquista e do riso. Uma cor cantante, ardente, alegre (…). Lembra o sangue e incita à vitória. Durante o Estado Novo, foi difundida a ideia de que o verde representava as florestas de Portugal e de que o vermelho representava o sangue dos que tinham morrido pela independência da Nação. As cores da bandeira podem, contudo, ser interpretadas de maneiras diferentes, ao gosto de cada um.

No seu centro, encontra-se o escudo de armas portuguesas (que se manteve tal como era na monarquia), sobreposto a uma esfera armilar, que veio substituir a coroa da antiga bandeira monárquica e que representa o Império Colonial Português e as descobertas feitas por Portugal.

Os cinco pontos brancos representados nos cinco escudos no centro da bandeira fazem referência a uma lenda relacionada com o primeiro rei de Portugal. A história diz que antes da Batalha de Ourique (26 de Julho de 1139), D. Afonso Henriques rezava pela protecção dos portugueses quando teve uma visão de Jesus na cruz. D. Afonso Henriques ganhou a batalha e, em sinal de gratidão, incorporou o estigma na bandeira de seu pai, que era uma cruz azul em campo branco.

Outra explicação aponta ainda para o uso da bandeira em escudos; a cruz azul teria pintados (ou incorporados) pregos brancos para a segurar ou pinturas brancas, podendo já aludir às chagas de Cristo. Esta decoração nos escudos sofreria danos com as batalhas e com o tempo, deixando apenas o azul envolto com os pregos ou pinturas de branco, dando a ilusão dos actuais escudos azuis com as (actualmente) 5 quinas em cada um.

Há ainda a referência que, segundo a lenda, o número das quinas (5) e dos besantes (25) estão relacionados com os 30 dinheiros que Judas terá recebido pela traição a Jesus Cristo.[1]

Tradicionalmente, os sete castelos representam as vitórias dos portugueses sobre os seus inimigos e simbolizam também o Reino do Algarve. No entanto, a verdade é que os castelos foram introduzidos nas armas de Portugal pela subida ao trono de Afonso III de Portugal. Este rei português não podia usar as armas do irmão, D. Sancho II, sem diferença por não ser filho primogénito de D. Afonso II. Adoptou assim as armas de sua mãe que era castelhana, sendo que a bandeira de Castela, à data, era composta por um fundo vermelho e três filas e três colunas de castelos dourados. Há quem considere que, com a subida ao trono de D. Afonso III, e já na qualidade de rei, este deveria ter abandonado as suas armas pessoais e usado as do pai e do irmão.

Symbolism[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Portuguese flag displays three important symbols: the colours of the field, the armillary sphere and the national shield (these two make up the coat of arms).

Colors[editar | editar código-fonte]

The green and red colours that make up the background field hold a much more ambiguous and mysterious meaning than the most common explanations. These explanations arose during the Estado Novo period, the nationalist authoritarian regime that held power from 1933–1974, and claim that the green represented hope and the red represented the blood of those who died serving the nation.[2] Some sources believe these noble meanings are far from being true and were nothing more than propaganda, to give an honorable justification to their choice.[3]

Despite the fact that these two colours were never part of the national flag until 1910, they were displayed in several historical banners during important periods. John I's banner included a green Aviz cross on the red bordure. The red cross of the Order of Christ was used over a white field as a naval pennon during the Discoveries (also frequently on the sails); a green background version was a popular standard of the rebellious during the 1640 revolution that restored Portugal's independence from Spain.[4] There are no registered sources to confirm that this was the origin of the republican colors; another explanation gives full credit to the flag that was hoisted on Porto's city hall during the 1891 insurrection. It consisted of a red field bearing a green disc and the inscription Centro Democrático Federal «15 de Novembro» (em inglês: Federal Democratic Center «15 of November»), representing one of many masonry-inspired republican clubs.[5] Over the following 20 years, the red-and-green was present on every republican item in Portugal.[6] The red, inherited from the 1891 flag, stands for the colour of the republican-inspired revolutionary, masonry, Green is the colour Auguste Comte had destined to belong in the flags of the positivist nations, an ideal incorporated into the republican political matrix.[6]

Armillary sphere[editar | editar código-fonte]

The armillary sphere was an important astronomical and navigational instrument for the Portuguese sailors who ventured onto unknown seas during the Age of Discoveries. It became the symbol of the most important period of the nation — the Portuguese discoveries — and that is why King Manuel I, who ruled during this period, incorporated the armillary sphere in his personal banner.[7] It was simultaneously used as the ensign of ships plying the route between the metropolis and Brazil,[7] becoming the symbol of the colony and a fulcral element of the flags of the Brazilian kingdom and empire.

Adding to the sphere's significance was its common use on every manueline-influenced architectural work, where it is one of the major stylistical elements, such as the Jerónimos Monastery and Belém Tower.[8]

Portuguese shield[editar | editar código-fonte]

On the top of the armillary sphere rests the Portuguese shield. It is present in almost every single historical flag (except during the reign of Afonso I). It is the prime Portuguese symbol as well as one of the oldest, with the first elements of today's shield appearing under the reign of Sancho I.[9] The evolution of the nation's flag is inherently associated with the shield's evolution.

Inside the white inescutcheon, the five quinas (small blue shields) with their five white bezants are popularly associated with the "Miracle of Ourique".[10] The story linked to this miracle tells that before the Battle of Ourique (July 25, 1139), an old hermit appeared before Count Afonso Henriques (the future Afonso I) as a divine messenger. He foretold Afonso's victory and assured him that God was watching over him and his peers. The messenger advised him to walk away from his camp, alone, if he heard a nearby chapel bell tolling, in the following night. In doing so, he witnessed an apparition of Jesus on the Cross. Ecstatic, Afonso heard Jesus promising victories for this and future battles, as well as God's wish to act through Afonso and his descendants to create an empire which would carry His name to unknown lands, choosing the Portuguese to perform great tasks.[11]

Confident from this spiritual experience, Afonso won the battle against an outnumbering enemy. Legend has it that Afonso killed the five moorish kings of the Seville, Badajoz, Elvas, Évora and Beja taifas, before decimating the enemy troops. Hence, in gratitude, he incorporated five shields (the quinas) arranged in a cross — representing his divinely-led victory over the five enemy kings — with each one carrying Christ's five wounds in the form of silver bezants. The sum of all bezants (doubling the ones in the central quina) would give thirty, symbolizing Judas Iscariot's thirty pieces of silver.[11]

However, evidence pointing out that the number of bezants on each quina was greater than five, during long periods following Afonso I's reign,[10] as well as the fact that only in the 15th century was this legend registered on a chronicle by Fernão Lopes (1419),[12] helps support this explanation as one of pure myth with doubtful veracity and highly charged with patriotic feeling (the idea that the nation was born by divine intervention and was destined for great things).

The seven castles are traditionally considered a symbol of the Portuguese victories over their Moorish enemies, under Afonso III, who supposedly captured seven enemy fortresses in the course of his conquest of the Algarve, in 1249. Yet, this is nothing more than popular belief because this king did not have seven castles on his banner, but an unspecified number. Some reconstructions display about sixteen castles; this number changed to nine, in 1385, and was only fixed at seven, in 1485. An hypothesis about the origin of the castles on a red bordure lies in the connection of Afonso III with Castile (his mother and second wife), whose arms consisted of a yellow castle on a red field.[13]

Design[editar | editar código-fonte]

O decreto que substituiu a bandeira usada durante a monarquia constitucional pela nova bandeira Nacional foi aprovado pela Assembleia Constituinte e publicado no Diário do Governo no dia 19 de Junho de 1911. em 30 de Junho, este decreto teve seus regulamentos oficialmente publicadas no Diário Nacional de número 150.[14]

Construção[editar | editar código-fonte]

O comprimento da bandeira é de vez e meia a sua altura. O fundo é divido em duas cores fundamentais: Verde, no lado da tralha e escarlate. A divisão das cores é feita de forma que o verde ocupe 2/5 do comprimento e o escarlate 3/5 (em propoção de 2:3)[14] No divisão das duas cores, está o Brasão de armas de Portugal (na forma de armas menores).

A esfera armilar tem o diâmetro igual a metade da largura e está equidistante das bordas superior e inferior da bandeira.[14] A esfera, desenhada em perspectiva, possui seis arcos com bordas em alto relevo, os quais quatro são grandes círculos e dois são pequenos círculos. Os grandes círculos representam a eclíptica, o equador e dois meridianos. Os últimos três são posicionados de forma que os cruzamentos entre cada dois arcos resulte em um ângulo recto. Um meridiano esta situado soba bandeira enquanto os outros são perpendiculares a este plano. Os dois círculos menores representam os dois trópicos, cada um deles tangente a uma das intersecções eclíptica-meridianos.[15]

Vertically centered over the sphere is the national shield, a white-bordered curved-bottom ("Portuguese type") red shield charged with a white inescutcheon.[16] Its height and width are, respectively, seven-tenths and six-tenths of the sphere's diameter. The shield is positioned in a way that its limits intersect the sphere:[15]

- at the distal edge's inflection points of the Tropic of Cancer's posterior half and Tropic of Capricorn's anterior half (top and bottom);

- at the intersection of the lower edges of the ecliptic's posterior half and equator's anterior half (dexter or viewer's left side);

- at the intersection of the upper edge of the ecliptic's anterior half lower edge of the equator's posterior half (sinister or viewer's right side).

Um aspecto curioso é a ausência de um segmento do trópico de capricórnio entre o Brasão Nacional e o arco da eclíptica.[15]

The white inescutcheon is itself charged with five smaller blue shields (escudetes or quinas) with their curved edges pointing down and arranged like a greek cross (1+3+1). Each quina holds five white bezants displayed in the form of a saltire (2+1+2). The red bordure is charged with seven yellow castles:[16] three on the chief portion (one in each corner and one in the middle), two in the middle points of each quadrant of the curved base (rotated 45 degrees), and two more on each side of the bordure, over the flag's horizontal middle line. Each castle is composed by a base building, bearing a "closed" door (yellow-colored), on top of which stand three battlemented towers.[15]

A bandeira não tem a tonalidade de suas cores especificados em qualquer documento legal. Uma lista aproximada está descrita abaixo:[15]

| Esquema | Vermelho | Verde | Amarelo | Azul | Branco | Preto |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMS | 485 | 349 | 803 | 288 | — | Black |

| RGB | 255-0-0 | 0-102-0 | 255-255-0 | 0-51-153 | 255-255-255 | 0-0-0 |

| CMYK | 0-100-100-0 | 100-35-100-30 | 0-0-100-0 | 100-100-25-10 | 0-0-0-0 | 0-0-0-100 |

| Tripleto hexadecimal | #FF0000 | #006600 | #FFFF00 | #003399 | #FFFFFF | #000000 |

Background[editar | editar código-fonte]

With the Republican revolution of October 5, 1910, came the need to replace the monarchy's symbols, represented in the first instance by the national flag and anthem. The choice of the new flag was not without conflict, especially over the colours, as partisans of the republican red-and-green faced opposition from supporters of the traditional monarchical blue-and-white. Blue also carried a strong religious meaning as it was the colour of Our Lady of the Conception (em português: Nossa Senhora da Conceição), who was crowned Queen and Patroness of Portugal by King John IV, so the removal or substitution of this colour was justified by Republicans as one of the many measures needed to secularize the state.[6]

After much discussion and the presentation of many proposals,[17] a governmental commission was set up on October 15, 1910, that included Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro (painter), João Chagas (journalist), Abel Botelho (writer) and two military leaders of 1910: Ladislau Pereira and Afonso Palla.[6] This commission ultimately chose the red and green of the Portuguese Republican Party, delivering an explanation purely based on patriotic motives,[18] disguising the political significance behind the choice, as these were colours present on the banners of the rebellious, during the republican insurrection of January 31, 1891, in Porto, and during the monarchy-overthrowing revolution, in Lisbon.[19]

About red, the commission considered it should "(…) be present as one of the main colours, because it is the battling, warm, virile colour, par excellence. It is the colour of conquest and laughter. A singing, burning, joyful color (…) Recalls the idea of blood and urges to achieve victory". An explanation for the inclusion of the green colour was harder to come up with, given that it was not a traditional color of the Portuguese flag throughout its history. Eventually, it was justified on the grounds that, during the 1891 insurrection, this was the colour present on the revolutionary flag that "sparkled the redeeming lightning" of republicanism. Finally, white (on the shield) represented "a beautiful and fraternal colour, into which all other colours merge themselves, colour of simplicity, of harmony and peace", adding that "(…) it is this same colour that, charged with enthusiasm and faith by the red cross of Christ, marks the Discoveries epical cycle."[18]

The manueline armillary sphere, which had been present on the national flag, under the reign of John VI, was revived because it consecrated the "Portuguese epic maritime history (…) the ultimate challenge, essential to our collective life.". The Portuguese shield was also incorporated, this time positioned over the armillary sphere. Its presence would eternalize the "human miracle of positive bravery, tenacity, diplomacy and audacity that managed to bind the first links of the Portuguese nation's social and political affirmation", since it is one of the "most vigorous symbols of the national identity and integrity".[18]

The new flag was produced in large numbers at the Cordoaria Nacional (em inglês: National Ropehouse), and was officially presented nationwide, on December 1, 1910 (day of the restoration of independence), which had already been declared by the government as the "Flag Day" (currently not celebrated). In the capital, it was paraded from the city hall to the Restauradores (em inglês: Restorers) Monument, where it was hoisted. This festive presentation did not disguise, however, the turmoil caused by a flag chosen without any popular consultation and that represented the political regime, instead of the nation. To encourage a greater acceptance of the new flag, the government issued all teaching establishments with one exemplar, whose symbols were to be explained to the students; textbooks were changed to intensively display these symbols. Also, 1 December ("Flag Day"), January 31 and October 5 were declared national holidays.[19]

Evolution[editar | editar código-fonte]

Since the foundation of Portugal, the national flag was always linked to the royal arms and, up until 1640, there was no official distinction between both.[20] It evolved in a way that gradually incorporated most of the symbols present on the current coat of arms.

1095–1248[editar | editar código-fonte]

|

|

|

The first heraldic symbol that can be associated with what would become the Portuguese nation was on the shield used by Henry of Burgundy, Count of Portugal since 1095, during his battles with the Moors. This shield consisted of a blue cross over a white field.[21] Nevertheless, this design has no reliable sources since it is a reconstruction that became popular and widely accepted thanks to the nationalistic purposes of the Estado Novo regime.[19] It has resemblances with the old naval flag of Corunha, in nearby Galiza, derived from the cross of Saint Andrew, and itself the basis for present-day national flag of Galiza.[22]

Henry's son Afonso Henriques succeeded him in the county and took on the same shield. In 1139, despite being outnumbered, he defeated an army of Almoravid Moors at the Battle of Ourique and proclaimed himself Afonso I, King of Portugal, in front of his troops. Following the León official recognition, in 1143, Afonso changed his shield in order to reflect his new political status. Sources state he charged the cross with five sets of eleven silver bezants (most likely large-headed silver nails), one set on the center and one on each arm, symbolizing Afonso's newly-gained right to issue currency.[23][21]

During the reign of Afonso I, it was not usual to repair battle damages inflicted on the shield, so changes such as loss of pieces, colour shifting or stains were very common. When Sancho I succeeded his father Afonso I, in 1185, he inherited a very worn off shield — the blue-stained leather that made the cross had been lost except where the bezants (nails) held it in place. This involuntary degradation was the basis for the next step on the evolution of the national coat of arms, where a plain blue cross transformed into a compound cross of five blue bezant-charged escutcheons — the quinas were thus born.[23][21] Sancho's personal shield (called "Portugal ancien"[9]) consisted of a white field with a compound cross of five quinas (each one charged with eleven silver bezants) with the bottom edges of the lateral ones facing towards the center. Both Sancho's son Afonso II and grandson Sancho II used these arms,[21] as it was usual with direct succession lines (cadency system). A new modification of the royal arms was made when Sancho II's younger brother became king, in 1248.

1248–1495[editar | editar código-fonte]

|

|

|

Afonso III of Portugal was not the eldest son, therefore heraldic practices stated he should not take his father's arms without adding a personal variation. Before becoming king, Afonso was married to Matilda II of Boulogne but her inability to provide him with a royal heir led Afonso to divorce her, in 1253. He then married Beatrice of Castile, an illegitimate daughter of Alfonso X of Castile. It is more likely that it was this family connection with Castile (his mother was also Castilian) that justified the new heraldic addition to the royal arms — a red bordure charged with an undetermined number of yellow castles — rather than the definitive conquest of the Algarve and its Moorish fortresses, considering that the number of castles was only fixed in the late 16th century.

The inner portion contained the arms of Sancho I, although the number of bezants varied between seven, eleven and sixteen (the latter number was used on Afonso's personal standard while he was still Count of Boulogne).[21] This same design was used by the Portuguese kings until the end of the first dynasty, in 1383; a succession crisis put the country at war with Castile and left it without a ruler for two years.

In 1385, in the wake of the Battle of Aljubarrota, a second dynasty was founded when John, Master of the Order of Aviz and illegitimate son of King Peter I, acceded to the throne as John I. To his personal banner, John I added his Order's fleur-de-lys cross, displayed as green flowery points on the red bordure; this inclusion reduced the number of castles to twelve (three around each corner). The number of bezants in each escutcheon was reduced from eleven to seven.[21] This banner lasted a hundred years until John I's great-grandson John II restyled it, in 1485, introducing important changes — the removal of the Aviz cross, a downward arrangement and edge-smoothing of the quinas, and the definitive fixing of five saltire-arranged bezants in each quina and seven castles on the bordure (as it is currently).[24] John II's banner was the last armorial square banner used as the "national" flag or standard.[21] Following his death, in 1495, radical changes were made by his successor.

1495–1667[editar | editar código-fonte]

|

|

|

John II was succeeded by his first cousin Manuel I, in 1495. This king was the first to convert the traditional square armorial banner into a rectangular (2:3) field with the coat of arms on its center. Specifically, the flag was now a white rectangle centrally charged with the coat of arms (bearing eleven castles) on an ogival or heater-shaped shield and surmounted by an open royal crown.[21] This flag was used exclusively as the kingdom's banner since Manuel I possessed a personal standard which included the armillary sphere for the first time.[25]

In 1578, during the reign of Sebastian and on the eve of the fatal Battle of Alcácer Quibir, the flag was again modified. The number of castles was permanently fixed at seven and the royal crown was converted into a closed three-arched crown, which symbolized a stronger royal authority.[21] With Sebastião's death and the short-lived reign of his great-uncle Cardinal Henry, in 1580, a dynastic crisis was solved with the Spanish king Philip II acceding to the Portuguese throne as Philip I, installing a Spanish dynasty. The accession was made on the condition that Portugal was ruled as a separate, autonomous state, not as a province. This was fulfilled as Portugal and Spain formed a personal union under Philip I and his successors. A consequence of this administrative situation was the maintenance of the flag created under Sebastian's reign as the Portuguese national flag, while Spain had its own.[21] As the ruling house in Portugal, the Habsburg banner also included the Portuguese arms.[26]

The country regained its independence from Spain, in 1640, in a coup d'état that placed on the throne John, Duke of Bragança, as King John IV. Under his rule, the national flag was slightly changed — the ogival shield became a rounded one (so-called "Portuguese type" shield). It was from this reign forward that the royal arms and the kingdom's arms became separate banners.[21]

1667–1830[editar | editar código-fonte]

|

|

|

When Afonso VI's younger brother Peter II replaced him on the throne, in 1667, he adapted the flag's crown to fit the contemporary trends by transforming it into a five-arched crown.[27] The new flag did not remain unchanged for too long, as it was refurbished by Peter's son John V, after he took the throne, in 1707. Heavily influenced by the luxurious and ostentatious court of the French king Louis XIV, and by France's political and cultural impact in Europe, John V wanted to transpose such style into the country's coat of arms — a red beret was added under the crown and the rounded shield was converted to a samnitic ("French type") shield. Instated by an absolute monarch like John V, this flag endured through almost the entire absolutist period in Portugal — John V (1707–1750), Joseph I (1750–1777) and Maria I (1777–1816).[21]

At the time of Queen Maria's death, the royal family was living in Brazil, having fled from Portugal after it was invaded by Napoleon's imperial army, in 1807. The Portuguese colony had been elevated to kingdom, in 1815, and in doing so the ruler began using the title of monarch "of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves". Maria I's son John VI changed the nation's flag to reflect this new union — the coat of arms, whose shield became rounded again, now rested upon a blue-filled yellow armillary sphere (arms of Brazil) surmounted by the same beret-bearing five-arched crown.[21] Apart from the crown and white background, this flag is similar to the current one.

1830–1910[editar | editar código-fonte]

|

|

John VI died in Lisbon, in 1826. His elder son Peter, who had declared the independence of Brazil, in 1822, becoming Emperor Peter I, succeeded on the Portuguese throne as Peter IV. Because the new Brazilian constitution did not allow further personal unions of Portugal and Brazil, Peter abdicated the Portuguese crown in favor of his elder daughter Maria da Glória, who became Maria II of Portugal. She was only seven years old, so Peter stated she would marry his brother Miguel who would act as regent. However, in 1828, Miguel deposed Maria and proclaimed himself king, abolishing the 1822 liberal constitution and ruling as an absolute monarch. This started the period of the Liberal Wars.[28]

The liberals formed a separate government exiled on the Azorian island of Terceira. It was this government that issued two decrees establishing modifications to the national flag. While supporters of usurper King Miguel I still upheld the flag established by John VI, the liberal supporters imposed important changes on it. The background was equally divided along its length into blue (hoist) and white (fly); the armillary sphere (associated with Brazil) was removed and the coat of arms was centered over the color boundary; and the shield reverted to the "French type" shape of John V. This new flag configuration was decreed solely for terrestrial use, but a variation of it was used as the national ensign. This ensign differed in the way the colors occupied the background (blue 1/3, white 2/3) with a consequent positional shift of the arms.[21]

With the defeat and exile of Miguel, in 1834, Queen Maria II was reinstated and the standard of the victorious side was hoisted in Lisbon as the new national flag. It would survive for 80 years, witnessing the last period of the Portuguese monarchy until its abolition, in 1910.

Flag protocol[editar | editar código-fonte]

Legislation[editar | editar código-fonte]

The constitutional legislation concerning the use of the national flag is rather scarce and incomplete. In some cases, it still dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. The regulations for its military and naval use, however, are more recent and complete.[29]

A revision of the decree no. 150, published on March 30, 1987, states that the flag is to be hoisted from 9:00 a.m. to sunset (during the night, it must be properly lit), on Sundays and national holidays, throughout the entire national territory. It can also be displayed on days where official ceremonies or other solemn public sessions are held — in this case, the flag is hoisted on-site. The flag can be hoisted in other days if it is considered appropriate by the central government, or by other regional or local governing bodies, or by heads of private institutions. It must follow the official design standard and be preserved in good condition.[29]

On the headquarter buildings of sovereign bodies, the flag can stay hoisted on a daily basis. It can also be hoisted on civilian and military national monuments; on public buildings associated with the central, regional or local administration; and on headquarters of public corporations and institutions. Citizens and private institutions can also display it, on the condition that they respect the relevant legal procedures. In the facilities of nationally-based international organizations or in the case of international meetings, the flag is hoisted according to the protocol used on those situations.[29]

If national mourning is declared, the flag will be flown at half-staff during the fixed amount of days; any flag hoisted along with it will be flown in the same manner.[29]

When unfurled in the presence of other flags, the national flag must not have smaller dimensions and must be situated in a prominent, honorable place, according to the relevant protocol:[29]

- Two flagpoles — right pole viewed by a person facing the exterior;

- Three flagpoles — central pole;

- More than three flagpoles:

- Within a building — if odd number of poles, central pole; if even number, first pole on the right of the central point;

- Outside a building — always the rightmost pole;

If flagpoles are not level, the flag must occupy the highest pole. The poles should be placed in honorable locations of the ground, building façades and roofs. On public acts where the flag is not hoisted, it can be suspended from a distinct spot, but never used as decoration, covering or for any purpose that can diminish its dignity.[29]

Penalties[editar | editar código-fonte]

An early decree, from December 28, 1910, established that "any person who, through speech, published writings or any other public act, shows lack of respect to the national flag, which is the motherland's symbol, will be sentenced to a three to twelve-month prison term with corresponding fine and, in case of relapse, will be sentenced to exile, as stated in the 62nd article of the Penal Code". In its 332nd article, the current penal code punishes infractors with a prison sentence of up to two years or a fine of up to 240 days. In case the offense is directed towards regional symbols, these previously mentioned penalties are applied with only half the duration.[30]

Folding[editar | editar código-fonte]

During formal occasions, four people are required to properly fold the flag, where each person holds one of the sides. A correctly folded flag must be a square limiting the national shield. However, the order by which the different folding steps are performed to achieve this result is not legislated.[31]

The procedure begins with the flag fully extended and held in an horizontal plane with the obverse facing down. One of the possible folding sequences is demonstrated below:[31]

| Stage | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| First | The upper third of the flag's height is folded into the reverse side until the crease is positioned over the shield's upper edge line. |

|

| Second | The lower third of the flag's height is folded into the reverse side until the crease is positioned over the shield's lowest point. | |

| Third | The folding proceeds along the width axis, with the fly's (red) union with the hoist (green) and the fold's placement over the shield's right edge. | |

| Fourth | Finally, the hoist is folded in a way that the resulting crease lies on top of the shield's left edge. |

Other flags[editar | editar código-fonte]

| Estandarte Nacional[32] | |

|---|---|

![Estandarte Nacional[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Military_flag_of_Portugal.svg/184px-Military_flag_of_Portugal.svg.png)

| |

| Aplicação | |

| Proporção | 12:13 |

| Adoção | 30 de Junho de 1911 |

| Tipo | nacionais |

Besides the state and civil flag, Portugal has a specific war flag which represents the national military forces on land (note, however, that it is the state flag, and not the war flag, that is flown on military buildings and facilities. The war flag is mostly used on parades).

Other flag variants are used by different high-ranked state offices connected to the government and the armed forces:

War flag[editar | editar código-fonte]

The national standard used by the Portuguese Armed Forces (em português: Forças Armadas Portuguesas) differs from the one used as civil flag, state flag, and national ensign. The military, also adopted, in 1911, is a rectangle measuring 1.20 metres (3.94 ft) in width and 1.30 metres (4.26 ft) in length (ratio 12:13). Green and red, are positioned at the hoist and fly, respectively, but occupy the background field in an equal manner (1–1). Centered over the color boundary lies the "major" version of the coat of arms — the armillary sphere and Portuguese shield are enclosed by two yellow laurel shoots intersecting at their stems and bound by a white scroll bearing the verse by Luís de Camões "Esta é a ditosa pátria minha amada" (em inglês: "This is my beloved fortunate motherland") as the motto. The sphere's outer diameter is ⅓ of the width and lies 35 centimetres (14 in) from the upper edge and 45 centimetres (18 in) from the lower edge.[14] When used as the "color" of a military unit, it is a gold-fringed 1.25 metres (4.10 ft) square placed on a lance-pointed staff engraved with the unit's name (or abbreviation), and adorned with red, green and golden tassels.[33]

[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Portuguese naval jack (jaco or jaque) is only hoisted at the prow of docked or anchored Navy ships, from sunrise to sunset. The national flag is permanently hoisted at the stern, when sailing, and from sunrise to sunset, when docked.[34] It is a square flag (ratio 1:1) bearing a green-bordered red field with the minor coat of arms on the center. The width of the green border and the diameter of the armillary sphere are equal to 1/8 and 3/7 of the side's dimension, respectively.[14]

Governmental flags[editar | editar código-fonte]

Some high-ranked officials of the Portuguese State have the privilege to display a personal flag representative of their position. The President of Portugal (em português: Presidente da República) uses a flag largely similar to the national flag, except for having dark green as the only background color.[35] It is usually hoisted at the President's official residence, the Palace of Belém, as well as on the presidential car, as small-sized flags. The flag of the Prime-Minister is a white rectangle (ratio 2:3) with a dark green saltire, holding the minor coat of arms on its center, and a red bordure charged with a pattern of yellow laurel leaves. Other ministerial flags do not possess the red bordure.[35] The flag of the Assembly of the Republic (em português: Assembleia da República) is also a white rectangle (ratio 2:3) with a centrally positioned minor coat of arms and a dark green bordure.[36]

|

|

|

|

| President of the Republic | Assembly of the Republic | Prime Minister | Minister |

See also[editar | editar código-fonte]

References[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ Conhecer - Bandeira e Hino, Impala Editores, 2004, página 15, ISBN 972-766-779-1

- ↑ «Symbolism». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 2 de março de 2007

- ↑ Martins, António. «Origins of the current Portuguese national flag». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 26 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Christ Knights' Order (Portugal)». Flags of the World. Consultado em 26 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Portuguese republican flags (1910ies)». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 1 de março de 2007

- ↑ a b c d Viana, Lomba. «Do azul-branco ao verde-rubro. O simbolismo da bandeira nacional». Símbolos (em Portuguese). Consultado em 26 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b Martins, António. «Bandeiras navais históricas». Bandeiras de Portugal (em Portuguese). Bandeiras do Bacano. Consultado em 24 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Monastery of the Jerónimos and Tower of Belém in Lisbon». Heritage. IPPAR - Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico. Consultado em 5 de março de 2007

- ↑ a b Martins, António. «Portugal (1185–1248)». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 22 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b «A Bandeira de Portugal». Portugal (em Portuguese). Criar Mundos. 2005. Consultado em 19 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b «Lenda do Milagre de Ourique». Lendas do distrito de Beja (em Portuguese). Lendas de Portugal. Consultado em 24 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Ourique, legend and future». "A Alma e a Gente". RTP. 19 de dezembro de 2006. Consultado em 25 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ Martins, António. «Portugal (1248–1835)». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 22 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b c d e «Decreto que aprova a Bandeira Nacional». Símbolos Nacionais. Portal do Governo. Consultado em 30 de Janeiro de 2009

- ↑ a b c d e «Bandeira nacional da República Portuguesa - desenho». Símbolos da República. Presidente da República, Jorge Sampaio (1996–2006). Consultado em 6 de abril de 2008

- ↑ a b Martins, António. «Bandeira de Portugal». Bandeiras de Portugal (em Portuguese). Bandeiras do Bacano. Consultado em 18 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Proposals for the new Portuguese national flag (1910–1911)». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 1 de março de 2007

- ↑ a b c «A Bandeira Nacional». Símbolos (em Portuguese). Ministério da Defesa Nacional. Consultado em 18 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b c «Bandeiras de Portugal» (em Portuguese). Acção Monárquica Tradicionalista. Consultado em 19 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ Martins, António. «Estandartes dos reis portugueses». Bandeiras de Portugal (em Portuguese). Bandeiras do Bacano. Consultado em 21 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Martins, António. «História da Bandeira de Portugal». Bandeiras de Portugal (em Portuguese). Bandeiras do Bacano. Consultado em 21 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «The Galician National Flag». Consultado em 10 de junho de 2007

- ↑ a b «Portuguese coat of arms». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 21 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ Candeias, Jorge. «Portugal - 1485 historical flag». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 22 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ Martins, António. «Estandartes dos reis portugueses». Bandeiras de Portugal (em Portuguese). Bandeiras do Bacano. Consultado em 1 de março de 2007

- ↑ «Royal Standards 1580–1700 (Spain)». Spain. Flags of the World. Consultado em 5 de março de 2007

- ↑ Martins, António. «Portugal - 1667 historical flag». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 23 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ Thomas, Steven. «Chronology: 1826–34 (Portugal's) Liberal Wars». Luso-Spanish Military History and Wargaming. Consultado em 5 de março de 2007

- ↑ a b c d e f «Regras que regem o uso da Bandeira Nacional». Símbolos Nacionais (em Portuguese). Portal do Governo. Consultado em 27 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Símbolos Nacionais» (em Portuguese). Presidency of the Portuguese Republic. Consultado em 2 de abril de 2008

- ↑ a b Jorge Candeias; António Martins (19 de dezembro de 1999). «How to fold the portuguese national flag». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 20 de julho de 2008

- ↑ «Símbolos Nacionais». Consultado em 30 de Janeiro de 2009.

Também chamado de Bandeira Militar de Portugal.

- ↑ «Military flags of Portugal». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 27 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ «Distintivos» (em Portuguese). Associação Nacional de Cruzeiros (A.N.C.). 14 de outubro de 1997. Consultado em 27 de fevereiro de 2007

- ↑ a b «Portuguese governmental flags». Portugal. Flags of the World. Consultado em 1 de março de 2007

- ↑ «Nova bandeira da Assembleia da República.». Portugal (em Portuguese). RTP. Consultado em 22 de maio de 2007

Further reading[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Coelho, Trindade (1908). Manual político do cidadão portuguêz (em Portuguese) 2nd ed. ed. Porto: Emprésa Litteraria e Typographica. OCLC 6129820

- Pinheiro, Columbano Bordalo. Bandeira Nacional: Modelo approvado pelo Governo Provisorio da Republica Portuguesa (em Portuguese) 1st ed. ed. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional. OCLC 24780919

Ligações externas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Portugal em Flags of the World

- (português) Presidency of the Republic — Official portal

- (português) Museum of the Presidency of the Republic