Roger Shepard

| Roger Shepard | |

|---|---|

| Shepard na conferência da ASU SciAPP em março de 2019 | |

| Nome completo | Roger Newland Shepard |

| Nascimento | 30 de janeiro de 1929 (95 anos) Palo Alto, Califórnia, Estados Unidos |

| Ocupação | cientista cognitivo |

Roger Newland Shepard (nascido em 30 de janeiro de 1929) é um cientista cognitivo norte-americano e autor da "lei universal da generalização" (1987). Ele é considerado o pai da pesquisa em relações espaciais. Ele estudou a rotação mental e foi um inventor da escala multidimensional não métrica, um método para representar certos tipos de dados estatísticos em uma forma gráfica que pode ser apreendida por humanos. A ilusão de ótica chamada de mesas de Shepard e a ilusão auditiva chamada de tons de Shepard receberam seu nome.

Biografia

[editar | editar código-fonte]Shepard nasceu em 30 de janeiro de 1929 em Palo Alto, Califórnia. Seu pai era professor de ciência de materiais em Stanford.[1] Quando criança e adolescente, ele gostava de mexer em relógios antigos, construir robôs e fazer modelos de poliedros regulares.[2]

Ele frequentou Stanford como estudante de graduação, eventualmente se formando em psicologia[2] em 1951.[3]

Shepard obteve seu Ph.D. em psicologia na Universidade de Yale em 1955 sob Carl Hovland, e completou o treinamento de pós-doutorado com George Armitage Miller em Harvard. Posteriormente, Shepard foi para o Bell Labs e, em seguida, foi professor em Harvard antes de entrar para o corpo docente da Universidade de Stanford. Shepard é Professor Emérito Ray Lyman Wilbur de Ciências Sociais na Universidade de Stanford.[4]

Seus ex-alunos incluem Lynn Cooper, Leda Cosmides, Rob Fish, Jennifer Freyd, George Furnas, Carol L. Krumhansl, Daniel Levitin, Michael McBeath e Geoffrey Miller.

Pesquisa

[editar | editar código-fonte]Generalização e representação mental

[editar | editar código-fonte]

Shepard começou a pesquisar mecanismos de generalização enquanto ainda era estudante de graduação em Yale: [2]

Eu estava agora convencido de que o problema da generalização era o problema mais fundamental com que se confrontava a teoria da aprendizagem. Como nunca encontramos exatamente a mesma situação total duas vezes, nenhuma teoria de aprendizagem pode ser completa sem uma lei que rege como o que é aprendido em uma situação se generaliza para outra.

Escala multidimensional não métrica

[editar | editar código-fonte]Em 1958, Shepard conseguiu um emprego na Bell Labs, cujas instalações de computador possibilitaram que ele expandisse o trabalho anterior sobre generalização. Ele relata: "Isso levou ao desenvolvimento de métodos agora conhecidos como escalonamento multidimensional não-métrico – primeiro por mim (Shepard, 1962a, 1962b) e, em seguida, com melhorias, por meu colega matemático do Bell Labs Joseph Kruskal (1964a, 1964b)."[2]

De acordo com a American Psychological Association, "o dimensionamento multidimensional não-métrico... forneceu às ciências sociais uma ferramenta de enorme poder para descobrir estruturas métricas a partir de dados ordinais sobre semelhanças."[5]

Rotação mental

[editar | editar código-fonte]

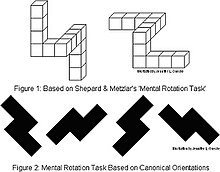

Inspirado por um sonho de objetos tridimensionais girando no espaço, Shepard começou a projetar experimentos[2] para medir a rotação mental em 1968. A rotação mental envolve "imaginar como seria um objeto bidimensional ou tridimensional se girado para longe de sua posição vertical original."[6]

Ilusões óticas e auditivas

[editar | editar código-fonte]

Em 1990, Shepard publicou uma coleção de seus desenhos chamada Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art.[7] Uma dessas ilusões ("Virando a mesa", p. 48) foi amplamente discutida e estudada como a "ilusão de mesa de Shepard" ou "mesas de Shepard". Outros, como o elefante que confunde figura-fundo que ele chama de "dilema L'egs-istential" (p. 79) também são amplamente conhecidos.[8]

Shepard também é conhecido por sua invenção da ilusão musical conhecida como tons de Shepard.[9]

Reconhecimento

[editar | editar código-fonte]A Review of General Psychology apontou Shepard como um dos mais "eminentes psicólogos do século 20" (55º em uma lista de 99 nomes, publicada em 2002).[10] As classificações da lista foram baseadas em citações de periódicos, menções em livros didáticos e nomeações por membros da American Psychological Society.[11]

Shepard foi eleito para a National Academy of Sciences em 1977[12] e para a American Philosophical Society em 1999.[13] Em 1995, ele recebeu a Medalha Nacional de Ciência.[4] A citação dizia: [14]

"Por seu trabalho teórico e experimental elucidando a percepção da mente humana do mundo físico e por que a mente humana evoluiu para representar objetos como o faz; e por dar um propósito ao campo da ciência cognitiva e demonstrar o valor de trazer os insights de muitas disciplinas científicas a serem utilizadas na resolução de problemas científicos."

Em 2006, ele ganhou o Prêmio Rumelhart.[4]

Ver também

[editar | editar código-fonte]Referências

- ↑ Seckel, Al (2004). Masters of Deception: Escher, Dalí & the Artists of Optical Illusion. [S.l.]: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 9781402705779.

Roger Shepard was born in Palo Alto, California. His father, a professor in materials science at Stanford, greatly encouraged and stimulated his son’s interest in science…

- ↑ a b c d e Shepard, Roger (2004). «How a cognitive psychologist came to seek universal laws» (PDF). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 11 (1): 1–23. PMID 15116981. doi:10.3758/BF03206455

. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019. I was now convinced that the problem of generalization was the most fundamental problem confronting learning theory. Because we never encounter exactly the same total situation twice, no theory of learning can be complete without a law governing how what is learned in one situation generalizes to another."

- ↑ «University of California Hitchcock Lectures». UCSB. 1999. Consultado em 15 de fevereiro de 2019.

Shepard graduated from Stanford in 1951, and received his doctorate from Yale. He then held positions at Bell Labs and at Harvard University before going to Stanford, where he has been a member of the faculty for over 30 years.

- ↑ a b c «2006 Recipient: Roger Shepard». Cognitive Science Society. 2006. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

Roger N. Shepard is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and is the William James Fellow of the American Psychological Association. In 1977 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 1995 he received United States’ highest scientific award, the National Medal of Science.

- ↑ No Authorship Indicated (1977). «Roger N. Shepard: Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award». American Psychologist. 32 (1`): 62–67. doi:10.1037/h0078482.

Recognizes the receipt of the American Psychological Association's 1976 Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award by Roger N. Shepard. The award citation reads: 'For his pioneering work in cognitive structures, especially his invention of nonmetric multidimensional scaling, which has provided the social sciences with a tool of enormous power for uncovering metric structures from ordinal data on similarities. In addition, his novel studies in recognition memory and pitch perception, and his latest innovative work on mental rotations--operations that may well underlie our ability to read and to recognize objects--have all contributed materially to our understanding of cognitive processes. His style of research exhibits a beautiful combination of depth and simplicity.'

- ↑ Kaltner, Sandra; Jansen, Petra (2016). «Developmental Changes in Mental Rotation: A Dissociation Between Object-Based and Egocentric Transformations». Adv Cog Psych. 12 (2): 67–78. PMC 4974058

. PMID 27512525. doi:10.5709/acp-0187-y.

. PMID 27512525. doi:10.5709/acp-0187-y. Mental rotation (MR) is a specific visuo-spatial ability which involves the process of imagining how a two- or three-dimensional object would look if rotated away from its original upright position (Shepard & Metzler, 1971). In the classic paradigm of Cooper and Shepard (1973) two stimuli are presented simultaneously next to each other on a screen and the participant has to decide as fast and accurately as possible if the right stimulus, presented under a certain angle of rotation, is the same or a mirror-reversed image of the left stimulus, the so called comparison figure.

- ↑ Shepard, RN (1990). Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art. [S.l.]: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0716721345.

Visual illusions, ambiguous figures, and depictions of impossible objects are inherently fascinating. Their violations of our most ingrained and immediate interpretations of external reality grab us at a deep, unarticulated level.

- ↑ Gifford, Clive (17 de novembro de 2014). «The best optical illusions to bend your eyes and blow your mind – in pictures». The Guardian. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

Famous impossible images include the Penrose staircase and this little beauty, courtesy of renowned cognitive scientist and author of ‘’Mind Sights’’, Roger Newland Shepard. With his usual love of a quick joke, Shepard entitled the illusion L’egs-istential Quandary. It is impossible to isolate the elephant’s legs from the background.

- ↑ Stephin Merritt: Two Days, 'A Million Faces' (video). NPR. 4 de novembro de 2007. Consultado em 9 de outubro de 2015

- ↑ Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). «The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century». Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139

- ↑ «Study ranks the top 20th century psychologists». APA Monitor. 2002. Consultado em 15 de fevereiro de 2019.

The rankings were based on the frequency of three variables: journal citation, introductory psychology textbook citation and survey response. Surveys were sent to 1,725 members of the American Psychological Society, asking them to list the top psychologists of the century.

- ↑ «Roger N Shepard». National Academy of Sciences. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

Election Year: 1977

- ↑ «American Philosophical Society Member History». American Philosophical Society. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

He is the recipient of the James McKeen Cattell Fund Award, the Howard Crosby Warren Medal from the Society of Experimental Psychologists, the Award in the Behavioral Sciences from the New York Academy of Sciences, the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award of the American Psychological Association, the Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology from the American Psychological Foundation, the Wilbur Lucius Cross medal of the Yale Graduate School Alumni Association, the Rumelhart Prize in Cognitive Science, and the National Medal of Science. He has also received honorary degrees from Harvard, Rutgers, and the University of Arizona.

- ↑ «The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details Roger N. Shepard». National Science Foundation. 2005. Consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2019.

For his theoretical and experimental work elucidating the human mind's perception of the physical world and why the human mind has evolved to represent objects as it does; and for giving purpose to the field of cognitive science and demonstrating the value of bringing the insights of many scientific disciplines to bear in scientific problem solving.